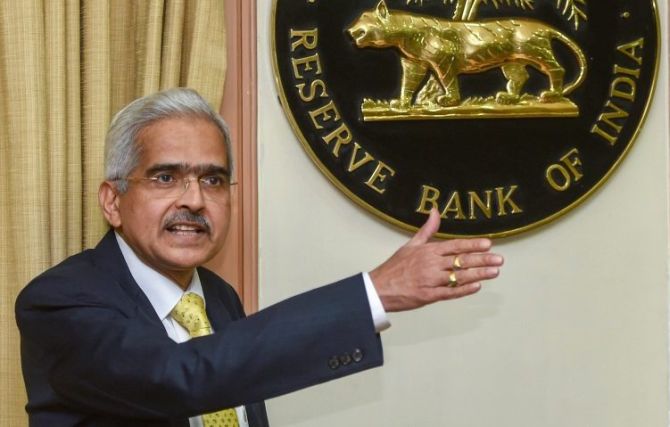

Speaking at the International Monetary Fund (IMF)-World Bank Spring Meetings in Washington recently, Reserve Bank of India Governor Shaktikanta Das made an extremely significant point, far reaching in its ramifications, and one that would have revolutionary implications for monetary policy worldwide. He asked Central Bankers all over the world to reflect on the conduct of monetary policy and not restrict themselves to the existing norms of oversimplified stances on policy direction and standardized 25 basis point tranches of policy action.

Governor Das explained that the current approach, followed by Central Banks worldwide, actually serves to deter policy, through an example: “If the easing of monetary policy is required but the central bank prefers to be cautious in its accommodation, a 10 bps reduction in the policy rate would perhaps communicate the intent of authorities more clearly than two separate moves – one on the policy rate, wasting 15 bps of valuable rate action to rounding off, and the other on the stance, which, in a sense, binds future policy action to a pre-committed direction.”

This leads us to reflect on why such a convention exists, and why we have persisted with it for so long. A logical conjecture that comes to mind is that it is a remnant of the unipolar economic world of the last quarter of the last century when the United States overwhelmingly dominated global markets both in terms of the volume of real as well as financial products. In those days it made eminent sense for all economic activity to be aligned, both operationally and conceptually to U.S. practices. Hence it made perfect sense for Europe, Japan, non-Japan Asia, Australia and the Emerging Markets to be in sync with the actions of the US Federal Reserve.

However, times are changing. Today the real and financial sectors in Asia are becoming increasingly more significant. We have argued that 30 years from now the Big Three in the world will be China, India and the U.S. Hence the classification of the world into G7, Emerging Markets and the arrangements of the last quarter of the 20 the century will be obsolete. In the coming world, using conventions of a previous age will be quite inappropriate at best and positively harmful at worst.

So do we need to use those conventions at all any longer? The answer is clearly no. The current approach is unwieldy and insufficient for the needs of the growth economies of today. Take India, for instance. The Governor cannot be hamstrung by being forced simply by convention to make a delayed impact instead of one that he is required to make instantaneously. The market he operates in is large enough and diverse enough to adjust to policy in extremely quick time.

In addition, India is clearly a supply side economy and rational expectations type policy is needed, and the old traditional post Keynesian policies of late 20 th century America. In such an economy the RBI Governor not only needs freedom of action but actually more empowerment. In terms of the actual operational conduct of monetary policy we feel that imitating US conventions with a voting Monetary Policy Committee is not optimal. Though we are all for a strong MPC, we feel it should have a strictly closed door advisory role to the RBI Governor. If the buck stops with him, there is no way his actions should be fettered in any form.

Governor Das is absolutely right. More power to him!

About the author : An alumni of Columbia University, Dr Ranjan Chakravarty heads Product Strategy at The Metropolitan Stock Exchange.